Kings Mills

For nearly two thousand years this little collection of islands, linked with the county of Berkshire, has been part of the main stream of English history.

Until the 1540’s the fortunes of the islands rose and fell with those of England’s Kings, for Temple belonged to the Bisham estate which was part of the Royal domain of William the Conqueror.

There have probably been settlements at Temple and Bisham since prehistoric times. There is evidence on the flood plain of the main river, in a great depth of peat, of remains of huge tree trunks and huge branches which may be part of a “considerable forest”. Not only did early man hunt for food here but settled for the first time by the old channel of the river. There was a time when the whole Marlow Valley, including the Temple Islands, was under the sea and the remains of sharks as well as mammoths have been found in the area. There is evidence of Celtic fields and farmhouses in the Valley and this land was owned by the Belgae tribe in the second century BC. Many Roman roads crossed the Thames’ Valley and there were Roman farms at Hambleden and Marlow, sending produce by river down to Londinium.

Though the Temple did not get its name until much later, there were probably mills at Bustlesham in Anglo-Saxon times. C J Cornish in “A Naturalist on the Thames” said that “fish and flour go together” and even before 1066 the river produced a valuable crop of fish.

William of Normandy

During the reign of Edward the Confessor, the Manor was held by Bondig, who was a horse Thane or constable. He was followed by Godric who was Sheriff of Berkshire. He may have been killed at the Battle of Hastings because he sided with Harold in his dispute with William of Normandy. He undoubtedly lost his Estate at Bisham after the conquest, for William gave it to one of his most stalwart supporters.

This was Henry de Ferrers, a poet and priest who came from Bayeaux and had fought with William at Hastings. He was one of William’s commissioners for the Domesday survey and held vast areas of land in fourteen different countries. He came into possession of Bisham in 1086. At Bisham the Domesday entry mentions “a vineyard, a church, two slaves and twelve acres of meadowland”. The estate was small and the lands very susceptible to flooding.

Henry was succeeded by his son Robert who, in 1138, had been made Earl of Derby by King Stephen. He decided to grant the manor to the Knights Templar. This was a monastic order of fighting Knights founded in Jerusalem as “Fellow Soldiers of Christ at the Temple of Solomon” soon shortened to Knights Templar. They had a Grand Master, Knights and Chaplains all of noble blood. In battle they asked and gave no quarter. The communities subordinate to the central house were called preceptories. There is a great deal of mystery surrounding the Templars and what they found in the Temple. After Henry I met their founder Hugh de Payans, the order became well established in England. Robert gave them Bisham “with church, wood, plain, meadows, pasture lands and mills that were to be enjoyed free and quietly”.

The Templars

The Templars also owned land at Widmer End and it was probably they who put a permanent bridge across the Thames at Marlow to connect their two preceptories. It is not clear where the exact location of the preceptory was. Some references suggest that it was actually at Temple and others in the area of Bisham Abbey, but from this time the mills are much in evidence.

Henry II confirmed the deed of Stephen and gave the Knights of the Temple “forty acres of cultivated forest land and the mills and fisheries of the said Manor”. Though the land was still held by the Templars in 1266, Edmund, second son of Henry III, was given Bisham. He was known as Crouchback and was the first member of the house of Lancaster to be connected with Bisham. Edmund’s son succeeded in 1277. Paying the King £46 for the estate.

Meanwhile, the Templars had become rich and powerful and this power was coveted by Kings and Emperors. Many false charges were levelled against them, and the French King Phillip IV persuaded the Pope, Clement V, to condemn them. Many were burnt at the stake and a general persecution of the Templars spread across Europe although the Templars in England still enjoyed the King’s favour. The master of the English Templars sat in Parliament as the Chief Clerical Baron of England and the King had obtained planks for the stands at his coronation from the Bisham Estate. For a time, Edward II resisted the tide against the Templars but in the end the Pope “directed” him to confiscate their lands and give them to the Knights of St John of Malta whose memory remains in the St John’s Ambulance Brigade. Edward obeyed but for some reason kept Bisham for himself. The Templars could not be accused of living in luxury at Bisham for the Estate, when taken over by the King, was valued at only £132.12s.7d. However, in 1309, there were three water mills at Temple.

The Mills

In these early days owners of mills wielded a great deal of power and, because they could control the flow of the water for their wheels, they also controlled the fisheries and the weirs.

At first, the holding back of water for mills was an aid to navigation as this reduced shallows but, as the mill owners and weir owners raised these obstructions, they became the occasion for great annoyance to riverside dwellers and to barge men, as they caused floods, and the price of tolls for a “flash” or flush of water to enable navigation to continue rose higher and higher. The mill owners also owned the land on either side of the river and, therefore, the fisheries. They sold fry of fish for manure and a “porkes a manger” at 1d per bushel. The cost of transport was increased and this put up the price of food. During the 1300 there were constant complaints about nets with small mesh, “divers ransomes” charged by mill owners and “boatmen in great peril of their lives” because of floods. But all petitions of the commons failed to subdue the power of vested interests as there was no authority to implement the various acts which were passed to limit the mill owners’ power.

Instead, from earliest days until the nineteenth century the owners of flash locks virtually controlled the river. They were loath to allow the water to go as it kept a head of power for the mill wheels. They sometimes charged for a “flash” and still kept the bargeman waiting. The flash lock at Shiplake was typical of all the locks until the pound locks were built in the 1700s.

The River Thames

The whole width of the river was blocked apart from a small section ten or eleven feet wide. Barges “flashed” downstream in the first rush of water and then those travelling upstream had to be hauled by men or horses and winches until the “water seller” closed the weir. There was a great waste of water and it could take two or three days to restore the level above the weir. This, of course, prevented the mills from working so it was not surprising that the mill owners were disinclined to let the water go.

Another problem was that at low water in summer the river became foul and stagnant. The Thames was the main sewer for the towns and cities on its banks and, though laws were passed from as early as the reign of Edward the Confessor to put down weirs and prevent “the casting of rushes, dung and refuse” into the river, as late as 1519 Oxford University complained that plague in the city was caused because the damming of the river prevented the drains being flushed in hot weather.

The River Tolls

Even Magna Carta declares in its twenty-third clause “Omnes Kidelli deponantor” but to no avail. The mill owners were still controlling their “flashes” and receiving their tolls up to the 1840’s. In fact in the Guild Hall Record Office List of old flash locks of 1848, Temple is noted as being owned by T P Williams who charged 3d per 5 tonnes of freight and this despite the fact that there was a pound lock close beside it. One of the problems faced by the commissioners was that the pound locks were kept by men in the pay of the mill owners and so it was not until the Thames conservancy was able to take over the locks that the landowners’ interest was removed.

The Bisham Estate

But, in the reign of Edward II, the mills were the property of the King. The wealth they generated made the Bisham estate a useful one for the King’s exchequer. He visited the manor in 1325 and in 1328 granted monies so that the river walls at Temple could be reinforced and the water mills repaired. There is frequent reference to the mills being “put down by floods”. The King also granted money to purchase a boat for the use of men towing barges upstream to Henley, presumably to enable them to return downstream.

However, all was not well with Edward. He was unpopular with both the Barons and his wife for his more than platonic relationship with Piers Gaveston. Gaveston gloried in his privileged position and stung the barons with his sarcasm. He made some formidable enemies for the King, notably the Duke of Lancaster who still held the nominal title to Bisham. Thomas of Lancaster made short work of Gaveston but lost his claim to Bisham on his own execution in 1322. This gave Edward the chance to give it to the son of Hugh le Despenser, his present favourite.

By this time the Queen had reached the end of her patience with Edward’s wayward sexual behaviour. She used the help of France to bring about his death and those of his favourites.

Edward III

Edward III, the new King, despite his youth, used the power of the Montacute family to establish himself on the throne and, after a short interlude when Ebulo d’Estrange – whose wife was the late Earl of Lancaster’s widow – held the manor, it was given to the Montacutes by the grateful young King. Montacute became Earl of Salisbury in 1337 and so began the long and bloody history of this formidable family at Bisham.

It was the Montacute family who restored Bisham to its religious foundation, granting the estate to the Austinor Black Friars who originated at Waltham Abbey. At this time it is clear that the abbey buildings and what we now know as Bisham Abbey are different, as the whole range of monastic buildings founded by William de Montacute in 1337 has been demolished and the new Abbey may have been built on the old foundations of the Templars’ building. However, from 1337 there was an Abbey at Bisham and a mansion. The remains of the Salisbury and later the Warwick family were all buried in the Conventual Church but this was also destroyed at the dissolution.

The Austin canons were granted the Manor by Royal Charter on 22nd April 1337. This gave the Prior many privileges including exemption from all tolls and taxes. In 1339 when the King’s estate keeper, John Hardyng died, the King granted his land to the friary. Further gifts of land were made and further tolls could be levied by them for the repair of Marlow bridge from 1400. By the dissolution, the estate was large, stretching from above Temple in the south to Cookham and even including areas in Maidenhead and Windsor. It also probably stretched across the valley on the Marlow side as the Templars had held Widmer End and later the estate clearly included Lane End.

So the mansion house was now in the hands of the Salisburys and presumably William left his wife Catherine there when he went to fight in France. His wife clearly did not lead the sheltered life of a war widow but assisted the king in his defeat of the Scots. It was after this that Edward is said to have fallen in love with her and, when she had the embarrassment of losing (or dropping) her garter at a royal ball, he is reputed to have returned it to her and uttered to the assembled company the famous words “Honi soit qui mal y pense”. In fact he was so infatuated with her that he founded the highest order of English chivalry and named it after this incident, thus demonstrating his devotion and gallantry (or so the romantic story has it).

The Earl of Salisbury was killed in a tournament at Windsor and his wife, who outlived him by six years, died in 1350. They were both buried in the Abbey Church at Bisham.

The second Earl, another William, was a leading figure on that glittering military stage dominated by the Black Prince. In fact, he fought by his side at Poitiers. However, on the death of the Black Prince, both he and his son, the third Earl, made the mistake of supporting the rightful but weak King Richard II, soon to be deposed and replaced by a previous owner of Bisham, the Earl of Lancaster. This was the redoubtable Henry Bolinbroke, later Henry IV.

The Holy Well

During this time, the people of Bisham and Temple were diverted by supernatural rather than national affairs. Rumour spread that the spring at the foot of the chalk escarpment was a holy well and its waters could cure blindness. Besides this miraculous water, there was a tame bird which nested in a tree nearby which allowed itself to be petted by the pilgrims. A hermit had set himself up by the well, living no doubt on alms from the “idolatrous multitude”. The Bishop of Salisbury (1375 – 88) condemned the proceedings; had the well filled with stones and the bird’s nesting tree cut down and burned. He threatened pilgrims with excommunication and the “idolatrous proceedings” ceased, no doubt much to the relief of the Austin Friars of Bisham and the Bishop who could once more collect the travellers’ monies which might otherwise have been thrown in the well.

But folk legend continued and when the water was analysed at the beginning of this century it was found to have gases suspending it which could have had a restorative effect on the eyes.

Henry V

John, the third Earl, continued to support Richard II and was finally beheaded by Henry IV. His body was buried at Bisham and the pious and guilt-stricken Henry V later sent his head to join it.

The fourth Earl, Thomas, though only twelve when his father was executed, was to become the most notable of all the Earls. He was at Harfleur with Henry V, perhaps even by the famous “breach. He was also one of the “band of brothers” at Agincourt, probably accompanied by many men from his estate at Bisham, and Temple, in fact, forty men at arms and eighty mounted archers. Shakespeare calls him the “mirror of all martial men” and puts him in the role of leaders that Henry V listed as in their flowing cups freshly remembered”. “Harry, the King, Bedford and Exeter, Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester”.

Despite his success as a field commander, a glorious return was not for Salisbury. He lost an eye and half his face at the Siege of Orleans when Jean D’Arc began to restore the fortunes of the French after their many humiliations under the Black Prince and Henry V. Salisbury died of his wounds and was buried at Bisham with part of his face covered.

Alice, his second wife, was not buried with him because she had married into the de la Pole family and is well known for her connections with Ewelme. Alice was a granddaughter of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer and her father had been speaker of the House of Commons in 1414. Her second husband was well connected with the Royal Family, having been in charge of Henry VI at the time of his coronation as King of France.

There are remarkable remains of the de la Poles at Ewelme. The oldest school in the county – still functioning as a school – and the oldest brick almshouse – both built by Alice. Her tomb is an alabaster masterpiece with remarkable details, one of which is the Garter Insignia which she wears on her left forearm. Both Queen Victoria and Queen Mary used Alice as an example of the correct position for the garter when worn by ladies. Alice’s family supported the Yorkist cause in the Wars of the Roses and most of them came to untimely ends.

Henry VI

In fact, the reign of the young Henry VI reversed the fortunes of England in France and, with no diversions on the continent, the powerful Houses of York and Lancaster fell to feuding. Henry, during his minority, had appointed his uncle, the Duke of York, as ‘protector of the realm’ but as a true Plantagenet and a descendent of Edward III he had a more powerful claim than this. The power vacuum which ensued during Henry’s bouts of madness and his talents for being a Saint more than a King in these crucial times, soon led to civil war.

Meanwhile, at Bisham the title of Earl of Salisbury was taken by the only daughter of Alice and the fourth Earl into the powerful Yorkist family of Neville when she married Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. He and his son were killed by the Lancastrian, Clifford, and their heads were spiked on York gates. This terrible news caused the death of the younger Alice and the title passed to her next son who became the famous ‘King Maker’. He continued the struggle against the Lancastrians, supporting Edward, son of Richard of York, who was still a minor. On their victory at Towton, Edward was crowned Edward IV and Warwick took over the direction of his affairs.

He was a great lover of the dramatic and even the melodramatic. He had stabbed his horse to death at Towton to show his men that he would not flee. He also organised an impressive spectacle for the funeral of his Father and Brother at Bisham. Their bodies were taken from Yorkshire and joined the coffin of Alice about a mile from Marlow. The chariot with the three coffins was followed by a resplendent Warwick at the head of sixteen knights. They were met at Bisham by three Bishops, innumerable Dukes and Earls, Heralds and Pursuivants. The whole ceremony lasted two days and was a remarkable spectacle of chivalry.

Warwick enjoyed the power he wielded but not so his protégé Edward IV. He wanted to become his own man and showed this by his secret marriage to Elizabeth Woodville who had connections with the Lancastrians.

The King’s Yorkist supporters were dismayed and looked to Warwick “to save England”. Warwick led a revolt against Edward, who fled abroad, and even restored the crazy Henry VI for a time.

But Edward was soon back with foreign support. Warwick and his brother John were both killed in the ensuing battle. Their bloodstained bodies were put on view in St. Paul’s for two days as an example of the fate of traitors and then two more bodies were dispatched to Bisham.

It is a rather gruesome thought to reflect how many famous corpses lie under the feet of the healthy and active sportsmen at Bisham, now striving hard to excel in the modern substitute for battle – international sport.

The Title and Estate of Bisham was now given by Edward IV to his brother George, Duke of Clarence – Shakespeare’s “false, fleeting, perjured Clarence”. He had married Warwick’s daughter and he plotted with everyone against everyone. He was offered a choice of deaths when his treachery landed him in the tower. The story has it that he jokingly asked to be drowned in a butt of Malmsey and his gaolers took him at his word.

The War of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses ended with the defeat of Richard III and Henry Tudor became Henry VII but doubts about the succession still lingered. Richard had been accused of murdering the two sons of Edward IV in the famous “Princes in the tower” scandal but, when one of them turned up as Perkin Warbeck, Henry VII began to be disturbed. He was also worried about Clarence’s son Edward who also had a legitimate claim to the throne, far better than that of Henry. He kept the young boy in the tower because a ten-year-old boy could not be charged with treason.

When Perkin Warbeck was also confined in the Tower they had adjoining cells. An informer said that Edward had communicated with Warbeck to wish him good spirits before he was hanged, drawn and quartered. Five days later Edward, Earl of Warwick, was also executed – another funeral at Bisham in 1499.

Henry VIII

Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509 and appeared the model of a perfect young King. He was a good Catholic and the Pope gave him the title of “defender of the faith” but he inherited his father’s unease about the Tudor succession. In fact, this unease became an obsession when his wife presented him with a daughter instead of the son he craved. By the 1530’s Henry had quarrelled with Rome and Thomas Cromwell was organising the seizure of Church lands. In 1536 two of his agents arrived at Bisham.

The Manor was held by Margaret, daughter of Clarence, and a good friend of Catherine of Aragon. She had petitioned parliament for restoration of her titles and, when Henry found her “the Saintliest woman in the world” he restored her title of Countess of Salisbury and most of her Estate at Bisham. He even made her the governess of his daughter, Mary.

The famous dove-cote with its potence, or revolving ladder, dates from Margaret’s time and she lived at the Mansion House at Bisham which stood close to the Augustin Priory.

The King had often hunted in the forest nearby and even came to Bisham to escape “the small-pox and measles but also the great sickness”. So great was his favour to Bisham that, not long after Cromwell’s henchmen had ‘dissolved’ the abbey and put in their own puppet as prior, Henry decided to restore it with monks from the Benedictine house at Chertsey. Henry had just lost his truly beloved Jane Seymour who had died in giving him the son he craved. He set up Bisham to pray for her soul.

Cromwell

But Cromwell was not moved by sentiment and in 1538 he took over the monastery despite Henry’s favour. The Abbey yielded him little for even the bells were rotten. Henry still visited the Mansion House at Bisham. He stayed in 1543 consuming “eggs and cream” but now the Countess of Salisbury was his problem. She was a staunch supporter of Rome. One of her sons was a Cardinal and he denounced Henry’s wayward marital practices. Henry retaliated by executing Margaret’s eldest son for high treason in 1538.

Next year Margaret was sent to the Tower where she stayed for two years. She was never tried but on 27th May 1541, though over seventy, she was beheaded. As a true Plantagenet she refused to kneel so the executioner performed his grisly task while the old lady stood proudly.

She was honoured by the Roman Catholic Church as one of the English Martyrs and is now known as Blessed Margaret Salisbury – the Saint of Bisham.

Bisham Abbey

Now the Estate was up for grabs. The despicable Richard Riche, one of Thomas More’s accusers, claimed it but the house, now called Bisham Abbey, was left uninhabited. It is difficult to discover what happened to the mills but they probably went on grinding corn for the King. Henry, by now old, sad and pox-ridden, was persuaded to marry Anne of Cleves. He couldn’t stand the sight of her and paid her off with various estates including Bisham and she still held it when Henry died.

But Anne probably wanted to be nearer her compatriots who were strong in the wool trade in East Anglia. She exchanged Bisham for an estate in Suffolk. Half the property figured in this exchange and went to the Hoby family. The other half, included the mills at Temple, she conveyed to her cofferer Thomas Persse.

And so, for the first time in their long history, the mills and Temple Mill Island have a history of their own quite separate from Bisham Abbey.

Merchants of Magnata

Since Anne of Cleves came from Flanders it is reasonable to assume that her cofferer had connections with the wool trade. The wool trade was the great industry of the 16th Century and many of the original open fields were being enclosed to feed sheep. The wool trade had enabled a growing number of its most influential merchants to form an affluent and important middle-merchant class. The ancient guilds, like the Mercers, obtained greater wealth and power. The English Company of Merchant Venturers had become the most important group of traders in Europe, having taken control of what was a prototype common market from the Hanse which had controlled trade in the 15th Century.

Merchant Venturers were importers and exporters. They had ships, they took risks and could wait for a return on their capital. For this they needed vast wealth and being a Merchant Venturer presupposed this. Antonio, the merchant of “Merchant of Venice” was typical of the class. The company of Mercers was the most powerful among the Merchant Venturers. They dealt in fine cloths, silks, velvets and luxury goods, but their main export was wool, though they made more profit from luxury cloth. There were merchants in other parts of the country but by 1497 the London Company of Merchant Venturers had in fact become a national company. By the middle of the 16th century their cloth exports alone amounted to over £1,000,000 per annum and after the accession of James I, they re-established themselves in Hamburg. They were then the trading masters of Europe.

John Brinkhurst Family

So, when we learn that Thomas Persse conveyed Temple Island and other areas to one John Brinkhurst, the Estate followed the trend of staying in the mainstream of English history because the Brinkhursts were Merchants. The first John Brinkhurst obtained from Thomas Persse in September 1544, “Temple Mills under one roof and fishery from Temple Locke to NW end of Westmeade”. The first John Brinkhurst is said to be a merchant of the staple – in other words, a wool merchant. The second John Brinkhurst was obviously the most affluent and powerful of this interesting family. There is an impressive brass in Bisham church which tells us a great deal about him in a few words.

The inscription reads:

“Here lieth the Bodye of John Brinkhurst, sometime citizen and Mercer of London and Merchant Venturer.”

He had progressed from “the staple” to being a member of the most important company of London. He was also a Merchant Venturer so he must have been very rich.

The Brinkhurst land included not only Temple Island but also the Bucks side of the river and they are deemed ‘gentlemen’ and said to come from Lane End, owning land called Moorland. It is a likely conjecture that one of the Brinkhurst houses was Moor Farm, now owned by Colonel and Mrs Green. John Brinkhurst was a public benefactor. The Marlow Archaeological Society quotes a stone in the churchyard which states: “John Brinkhurst, of Lane End in this parish, did in his lifetime found and endow the Four Alms houses in Oxford Lane, for four poor people above the age of Sixty Years with Five Shillings a quarter to be paid to each person, in the Church on the Friday after Candlemas day, May day, Lammas day and Allhallows”. The improved rents of the Estate amount to £29 per annum. Eventually two more were added when the ‘Estate’ produced £42 but all were demolished in 1969.

The brass in Bisham mentions John Brinkhurst’s two ‘wives’. The first was Elizabeth Blundell whom he married at Bisham in May 1567. She died in 1581. He then married Jane Woodford of Brightwell and she outlived him by two years, dying in 1616. Despite his two marriages and obvious great wealth he died childless, leaving his estates to his brother, Richard Brinkhurst. Unfortunately Richard predeceased him, leaving the estate to John’s nephew, Yet another Joyn, in 1614.

We have an administration of Richard’s will signed by his wife, Mary. He leaves an impressive number of goods and chattels, including many ‘blankets’ and ‘feather beds’. Each room, and there are many, is inventoried and then the farm buildings, including ‘the buttery’, ‘the brewhouse’ and the ‘yards’. The whole is signed and dated May 27th, 1642.

But soon dark clouds were gathering over the Brinkhurst family, despite the fact that they kept the estate for nearly a hundred years. The first hint of trouble comes from the blanks left in the Brisham brass. Spaces have been left to add the date of John Brikhurst’s death and that of his second wife, Jane. Both these spaces are left empty. Nobody has bothered to fill them in. Perhaps this is because the Brinkhursts, as a stalwart Catholic family, had become ‘persona non grata’ as papist recusants’!

The First Act of Uniformity was passed in 1559 but did not begin to bite until the reign of Elizabeth I.

Francis Colmer, by no means an altogether reliable historian, has taken the trouble to work out the Brinkhurst family from the Bisham parish records and there are interesting snippets of information in this, including what appears to be the Brinkhurst coat of arms. Some of them, it seems, returned to Germany, but the last John Brinkhurst name was attached to the entry “fined for recusancy” in 1652.

Odd glimpses of the family are revealed from a number of sources but, at the time of publication of this history, not enough time has been devoted to research into the really important details.

Owners of the Mill

They emerge as owners of the mills at Temple in a number of documents referring to the river. Bishop, in his various ‘complaints’ about the state of the river in 1580, mentions the lock and weir but these documents are difficult to read. The lock is said in 1580 to be in the ownership of “John Brynty gent” and later, “John —-rinky’s”. We also know that the manager of the mills at that time as well as “lock” keeper was one Richard Mathewe.

The parish registers are interesting from this time because they clearly state “at the mill” so we can see who the lock and mill keepers were and get some glimpses of life at the mills. The first family mentioned specifically “at the mill” are the Bowlers. The must have been a family of note for they owned some of the church rails and Widow Bowler remained at the mill after her husband’s death. She could afford servants because one of them, William Abraham, “washing himself was drowned at Temple Mill” in June 1579. In fact a number of people drowned at the ‘locke’ and mill – John Hampshire a Bargeman in November 1575 and Peter Allan “borne at London was drowned at Temple Mill and buried 6th July 1592”

Various names are mentioned in connections with the mills; the House family, the Overingtons, Haywards, Pitts and Forests but the only mention of the Brinkhursts seems to be in the Bucks Sessions records for every session from 1652 until the 1700s. The fines and penalties for “papist recusancy” were extremely harsh, ranging from 12d for each failure to attend church in 1581, to £20 a month and threat of confiscation of all goods and two thirds of lands if fines were not paid by 1587.

John Brinkhurst father and son are brought before the magistrates each quarter until they cease to be mentioned after 1701. Once John Brinkhurst is brought as a papist recusant though “a Beddrid man with the gout” – this is in October 1680. After his death, his widow and son continue to uphold the Catholic faith and she is last presented in October 1701, though “since deceased”.

By the early 18th century all their wealth and land must have gone together with the “carpets, feather beds” and the luxury they once enjoyed as powerful merchants.

Though no firm evidence has come to light, it may well be that, during the time of the Brinkhursts, the mills were used as filling mills. There is no reference to milling and the people in charge are never referred to as millers. Given the Brinkhursts’ connections with the wool trade this seems feasible, particularly as it is clear that by the 1720’s they were not concerned with corn but with manufacturing. At one time the mills manufactured tin plate and even put in a tender to produce currency but neither of these was successful. By 1720 they were producing a mixture of brass and copper utensils called Bisham Abbey Battery Ware but their ownership is doubtful.

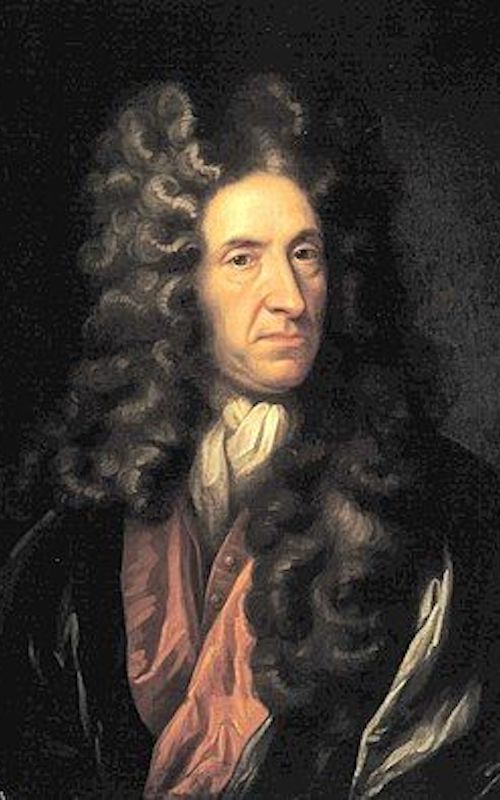

Daniel Defoe and the Mills

We get most information about Temple Mills in the early 18th century from Daniel Defoe who was most impressed with them when he visited during his tour of England and Wales in 1748.

He says “On the river of Thames, just by the side of the town (of Marlow) though on the other bank are the very remarkable mills which are called the Temple Mills, and are called also the Brass Mills and are for making Bisham Abbey Battery Ware as they call it; viz brass kettles and pans etc. of all sorts. They have first a foundry where by the help of lapis calimaris they convert copper into brass, and then having cast the brass into large broad plates, they beat them out by force of great hammers wrought by the water mills into what shape they think fit to sell ……Next to these mills both extraordinary in themselves, is one for making thimbles, a work excellently well finished and which performs to admiration, and another for processing the oyle from rape see and flax seed, both of which, I was told turn to very good account to the proprietors”.

And so the peaceful corn mills of the monks and friars have become the “dark, satanic mills” of the industrial revolution and the sights, smells and din emitted from this peaceful spot in the Thames is almost unbelievable.

But the other life of the river is still going on. Various fisheries are leased in exchange for a “good dish of fish at Christmas, Lady day and Michaelmas every year” and one Athaliah Rosewell lets the fisheries “from the upper end of Winchmead (we assume this was where the winch for hauling boats up the flash-lock was situated, probably on the site of Temple House? To the Marlow Bridge on the south side of the river”. This lease also includes “one little osier bed at Temple Mills containing nine poles”. This is probably the bed between the two mills tails which was roughly in the position of the centre pontoon in the marina now.

Osier beds were very valuable as the baskets made from the willows were shaped into fish and eel traps which brought in a good living from the river. The Rosewell family were famous fishermen on the Thames. There was then an island in the river just below Bisham Church, with the romantic name High Boughs. Obviously the Rosewells still had their fisheries lease as late as 1783 because one William Rosewell set up so many eel bucks to the island that he almost blocked the river, causing great havoc to navigation. The island was dredged away in 1893 preventing further danger.

In leasing her fisheries Athaliah also leases a ‘hop garden’, presumably on the south bank, and the leasees promise to keep it “dressed and manured”. They also promise to maintain the “Bucks, Weares, Wearborough and Sluices” on the river.

Influence of the Industrial Revolution

It is clear that the mills had become a separate entity from the lands surrounding them on the river. The owners were interested only in the profit from the various manufacturers made at the mills. The Industrial Revolution was here to stay. In fact the early years of the 18th century were troubled times for Temple Mills. In the journals of 1720 they are noted as being “among the bubbles of the time”.

Defoe mentions this in his ‘Tour’, saying of the Mills:

“But unfortunately the chief proprietors then being John Parry, Leonard Fletcher, John Shorey and Thomas Humphreyville turned it into what they call a bubble, brought it to Exchange Alley, set it a stock-jobbing in the days of our South Sea madness and brought it to be sold at £100 per share, who intrinsic worth was perhaps ten pounds, till with the fall of all these things, it fell to nothing again.”

There is a very interesting set of playing cards of the “bubble companies” and Temple Mills figures on the King of Diamonds. The picture is delightful and, though a cartoon, is perhaps the only picture of Temple Mills in their early days. It shows Bisham Abbey and Church in the background and the view is that from the west of the present marina. The huge water-wheel continued in this position until it was sold by the present developers. But as the verse notes “they still work on” and were working well when Defoe visited them in 1748.

William Ockenden

By this time, they had come into the ownership of William Ockenden. He had lived in Ireland but probably inherited the mills from his uncle Simes of Hurley. He continued to make brass and copper utensils and eventually became MP for Marlow – a tradition that was to be maintained by the mill owners for two centuries. He could influence the votes of his workmen so had a good chance of success. Ockenden vied with his neighbours in the Hoby family for the membership. He joined the part of Fredrick, Prince of Wales, and was “put down” for some place in the Ordnance in the next reign. He also owned mills in Weybridge when he died in 1761.

After William Ockenden’s death, the Temple Mills went to his nephew, George Pengree of Wittington, Medmenham. The family had copper interests in Cornwall as well as smelting houses in South Wales. These were the Middle Bank Works and the Upper bank works which were founded as Townsend and Co. but later became George Pengree and Co. All these interests were bought at a later date of firms controlled by “The Copper King” himself – Thomas Williams.

Thomas Williams

Thomas Williams would fill more than one book on his own and, indeed does, and although he really purchased Temple Mills for his eldest son, as a private company, to all intents and purposes it was part of his great copper empire. This empire also gave him important by-products like vitriol, the basis of the emerging chemical industry which later became ICI. He also controlled what later became the Pilkington Glass Works and was really the founder of the industrial revolution in South Lancashire.

So, once again, Temple Island has its place in the large pageant of British history, and plays its part as a most important pioneer of the industrial revolution.

But first to the redoubtable Mr Williams. He began as a country solicitor in Anglesey. By 1769 he was involved in lawsuits connected with the ownership of mineral rights on the Parys Mountain, about half a mile inland from the small Anglesey harbour of Amlwch. Up to 1761 most of the copper ore had come from deep mines in Cornwall, but it was always expensive as the deeper the workings the more difficult the extraction, at least before the invention of adequate pumping machines. In 1761 old copper workings, probably Roman, were found on Parys by the agent of Sir Nicholas Bayly, later the Earl of Uxbridge. The decision of Sir Nicholas to start mining without consultation with his neighbours led to the great lawsuit in which Thomas Williams acted for the Hughes family, co-owners of the Parys mountain. This legal contest was to last seven years but at the end of it the country lawyer was not only an expert in the mining of copper but a shrewd and accomplished businessman. By the early summer of 1774, Williams and Hughes had obtained an injunction against mining at Parys by Sir Nicholas and, before he could appeal against it, had started mining themselves, even using Sir Nicholas’ own tools. By 1776, agreement for joint working had been reached but Sir Nicholas decided to lease his interest to the London Banker, John Dawes. No sooner had Dawes obtained the lease for twenty-one years that he joined Hughes and Williams to form the Parys Mine Company and by 1778 the whole Anglesey mining interest was under control. The most ‘active’ partner was Thomas Williams and the Parys mine was very productive and easily worked. This was soon to bring William’s into conflict with the vested interest of Cornish miners and the associated smelters, whose products he could undercut at his pleasure. By 1787 he had virtually taken over the administration of the whole Cornish copper industry and by 1792 had the monopoly of copper mining and production in the whole Britain and this meant the largest in the world. The Cornish interests alone had a working capital of half a million pounds and also had two smelting works in Swansea, a group of mills at Holywell, smelting works in South Lancashire, copper warehouses in London, Birmingham and Liverpool, a chemical works in Liverpool and a Bank in North Wales.

The capital he controlled must have been very nearly £1,000,000,000. As a sideline, but of course a profitable one, and an interest for his eldest son, he also brought the two groups of Pengree mills at Wraysbury and at Temple. It is doubtful whether his family inherited their father’s entrepreneurial skill but he secured the prosperity of his eldest son by setting up Temple Mills as a partnership between Owen Williams and Pascoe Grenfell. This was a very sound move for Pascoe Grenfell was Williams’ chief assistant in the London Copper Office, a gifted salesman and an expert in the copper sheathing of navy and merchant ships

This became an important and expanding industry throughout the 19th century and even up to the building of ‘iron’ ships. Even today, boats are taken out of the water at intervals to be ‘antifouled’ with ‘hard racing copper’. This is vital for wooden boats and very desirable even for fibreglass and metal boats.

The reason for this is that the hulls of boats become covered with algae which seriously reduces their speed and efficiency and to prevent this, and attacks by worms, especially in seagoing boats and those which ply in tropical waters, the hulls are given a coat of copper-based paint. Ships had originally been sheathed with another of wood which could easily be replaced but ‘coppering’ was much more efficient and meant more money for the owners as the ships were faster and more manoeuvrable. It also meant a distinct advantage in war. Rodney affirmed that “copper-bottom ships are absolutely necessary”.

There was only one problem, however. Machinery was already in use, and at Temple Mills, which could roll out thin sheets of copper but these had to be nailed or bolted to the hull of the ship with iron bolts. Though the copper was impervious to rust, the iron deteriorated and the ship became like a pincushion and slowly sank to the bottom. Two famous French ships were sunk in this way as well as many others, as Thomas Williams himself reports to the parliamentary committee looking into the copper sheathing. Because of this, despite the early success of ‘coppering’, by 1782 the Admiralty feared that it would have to be discontinued.

Williams eventually found a solution by patronising an inventor of copper bolts and selling ‘Westwood and Collins Patent Bolts’. Westwood had invented a cold rolling method for copper bar which gradually reduced it by passing it through grooved rollers while drawing it out to the required thickness. In 1784, the Admiralty ordered all new ships to be fitted with these patent bolts. Williams sold both the copper and the bolts and he sold them through a travelling exhibition set up by Pascoe Grefell, to the French, Dutch and Spanish Navies.

Temple Mills international expansion

Temple Mills – export business! By the end of the century Temple Mills were booming. There were three mills, a hammer mill, a flat rolling mill and a bolt mill, providing fifty men and boys with full employment on ‘piece work’ and processing 600 – 1000 tons of copper each year.

The great ships of Nelson – and Napoleon – were probably sheathed with Temple copper and bolts as it was just a short voyage down the Thames to the Admiralty dockyards. It is a pleasant thought that Temple Island may have played its part in the victory of Trafalgar and the eventual defeat of Napoleon.

But Williams was not a fine minded patriot, he was mainly a businessman having “neither friends nor enemies – only interests”. He was just as enthusiastic about ‘copper-bottoming’ ships for the slave trade and, by 1900, his Liverpool agent was handling nearly 150 ships a year, many of them sailing in tropical waters and dealing in the slave trade. Grisly as this was, the coppering may have saved the lives of some of the slaves who were frequently lost in the rotten ships which took them from Africa to the West Indies.

The years after his purchase of Temple Mills in 1788 up to his death in 1802 were to some extent to see the decline of Williams’ copper empire but by then he could enjoy the wealth and pleasures of an Industrial Revolution baron, ranking with Boulton and Watt in importance as a hard businessman.

He bought the borough of Marlow so that he could vie with the powerful Clayton family of Harleyford as to who represented the town in Parliament. Many of his workers came from Marlow and he owned their houses. The Williams family were not averse to using eviction as a threat against a misplaced vote in the days before secret ballots. He brought in one of the renowned architects of the day, Samuel Wyatt, to renovate and enlarge Temple Mills and while he was in Williams’ employ he got him to design a huge mansion at Temple and build Marlow town hall which Williams donated to the grateful borough.

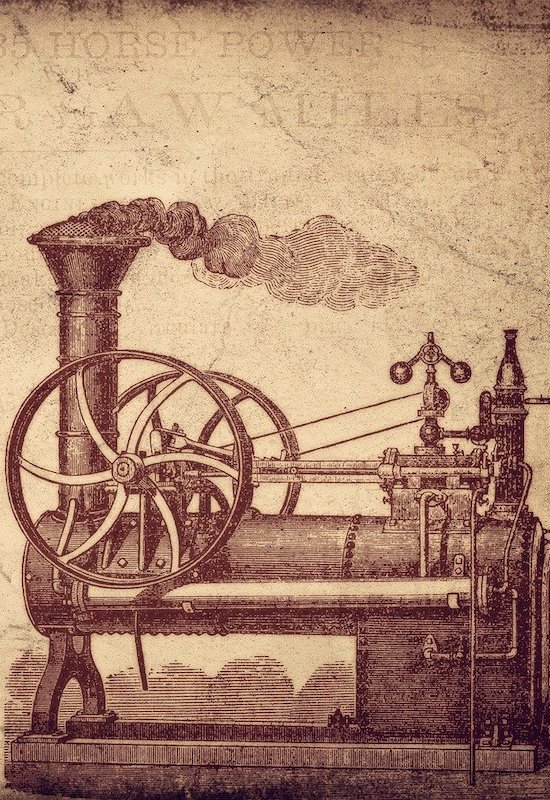

The design of the Mills

We are indebted to P G Wilson, who did a survey of the old mills before they were pulled down, for the details of Samuel Wyatt’s work at Temple.

There had, of course, been three mills on the site since medieval times but they had been used for many different purposes. The main mill buildings can be seen on what is the up-river side of the plan. The plan dates from 1849 when the mills were then paper-mills but a fairly clear idea of Wyatt’s mills can be obtained. The Clock Mill and the Bolt Straightening Mill were both completed by Wyatt about 1790. They were joined together as one. This building was always called the ‘old’ copper mill so was probably originally used for ‘battery’ work. However, it may have been adapted as a bolt making mill by Wyatt. It was a typical 18th century building with a pedimented front. It was of brick with moulded cornice and frieze. It had three windows and a turret with a wrought iron weathervane. The two storeys were supported by cast iron pillars and the roof of wooden rafters with massive horizontal squared beams which dated back to Wyatt’s day, as did the cast iron. At the top was a wooden clock room. The clock was inscribed “Edwd Tutet, London 1782”. The cupola was similar to the one on Marlow town hall, and the bell was dated 1790. In Williams’ day there may have been two wheels as this is indicated by the 1849 plan but in the 1970s only one remained. This was the famous Wyatt cast iron wheel.

This was in the south face and was an ‘undershot’ wheel. It was made of delicate caste iron 7.3m in diameter including floats and 1.4m in width. The inclined sluice gate was of wood raised by rack and pinion gearing which was still working in the 1970s.

The cast iron wheel was most interesting as it was dished. It was held rigid at its outer extremity by 32 wooden floats fixed to the centre wheel on oak arms. The float consisted of three elm boards and these could be quickly replaced if damaged by debris down the sluice. There was only 1 cm clearance between the brick floor of the tail race and the quickly rotating floats. This gave maximum efficiency but could also lead to damage of floats. This wheel may have generated about 100hp. Since there was a bolt mill in 1809 the long building on the plan was probably used for this purpose. The centre square building was the centrepiece of Wyatt’s design and mainly used as a showroom.

The two buildings which face south west into the upper mill stream were probably the hammer mill and float rolling mill. The one on the east side was a plain two storey building and was probably built by Samuel Wyatt about 1790. It had thick red brick walls and a slate roof. It also had an undershot wheel made of oak which gave the appearance of great strength. It was 5.55m in diameter excluding floats which were probably like the ones in the clock mill with 32 floats. It had a massive iron axle and was said to generate 100 hp.

The building called the ‘New Mill’ was built before 1849 but was probably the last to be built, maybe not by Wyatt. The wheels had already disappeared long before PG Wilson’s survey.

Temple Mill Buildings

Probably the most impressive of Wyatt’s buildings is called the New Salle. It was a large two story building with the ground floor ceiling supported on cast iron columns. The roof was made of large slates supported by a graceful series of cast iron hooped girders. This building was an experimental one according to Mr T M Robinson and because it contained no wood in its constructions was Wyatt’s attempt to create a completely fire-proof building. In fact, he took out a Patent for total iron construction in 1800. Each section had a ‘push’ fit with the next. The whole structure was held by pressure and tension and no fixings were used.

Wyatt was something of an expert in his use of slate. This probably came from Penrhyn where Wyatt’s son was an agent of a slate quarry. Williams also used this slate as slate slab fencing round his estate – tall slates along the footpath to Henley to keep out prying common eyes and shorter ones along the fields which now form the boundary with the bypass.

Some cottages and what are obviously the mill manager’s house, as well as stabling were remaining on the south side of the site.

When the mill buildings were demolished there was some attempt to keep the wheels to set up as features of the site, but the latest on these is that the wood wheel was sold to another mill and the cast iron wheel broken up for scrap.